Don’t Write Alone Where We Write

Where Manjula Martin Writes

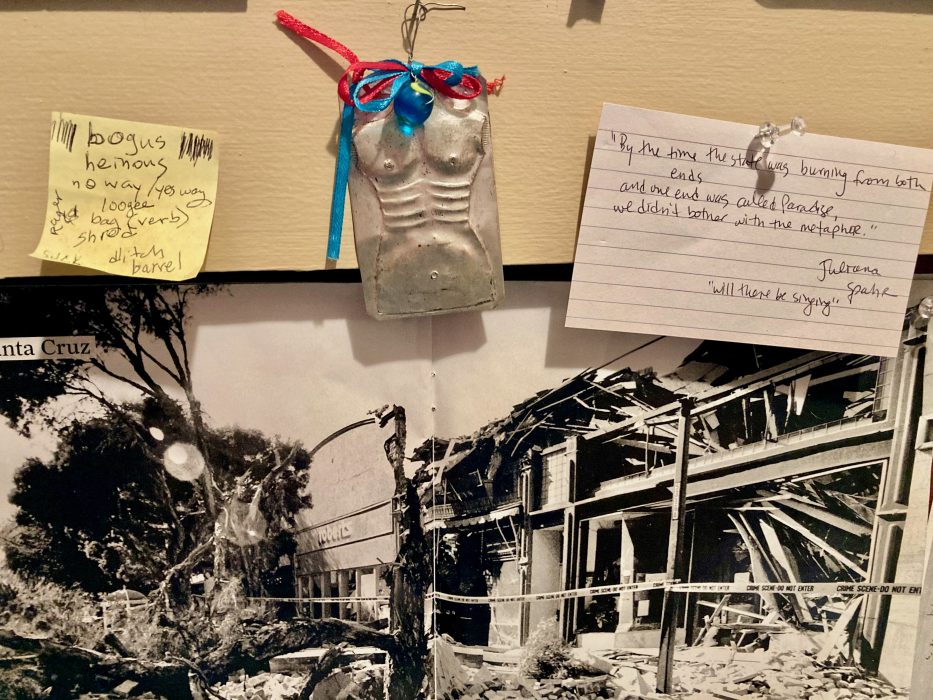

The room is my Narnia wardrobe, my Woolfian fantasy writ real, a masc womb of creative independence. I call the room The Lair because who wouldn’t.

North of a city, near an ocean, in a redwood forest on a hill, there is a small wooden house. Up the gravel drive, under the wisteria, just inside the front door, there is a closet door. Open it. Touch the coats and scarves that hang there like branches. Push them aside, step through, and you’ll enter a hidden room just big enough for a short woman to lie down in. This is where I write.

The room is my Narnia wardrobe, my Woolfian fantasy writ real, a masc womb of creative independence, and I can do whatever I want to it, because I own it and the house around it. If I am making this sound like a fairy tale, that’s because it feels like one, some days. Other days, when the heat waves creep through the single-pane windows and clamp around my neck, when the smoke clouds descend and the firehouse siren sounds, it feels like a different genre of story.

Photograph courtesy of the author

I never thought I would own a house in the woods—or, more accurately, I never thought I would pay a monthly sum of money to a financial institution whose name I barely know in exchange for permission to “possess” this building, these trees, the weird sinkhole in the garden that we keep pouring soil into, the raccoon who visits nightly and removes every single rock in the garden bed border and places it carefully just a few inches away. People call this process—slowly sending all your money to a corporation in exchange for many home repair tasks—building equity , which seems like an ironic word for it, but what do I know. I’m just lucky to be here.

When I say I never thought I’d buy a house, I don’t mean that in the boot-strappy, American-dream propaganda way. I mean that I didn’t think about it at all. I grew up in a house-shaped house in a town that celebrated its connection to nature: ocean, field, forest. But from the age of sixteen, I lived in big cities, expensive cities. I never had savings. I had approximately 479 jobs. No money was coming from any parents to me or my partner. I definitely didn’t know what soffits are.

Besides, I loved the city. How I loved the city. I loved the small box I lived in at its smelly, rainbow-painted heart. I adored those bay windows and green walls and my old writing space, which was a corner of my apartment’s living room. I never needed a whole room. But I did sometimes imagine what it might be like, to live in a house-shaped house again. I did often feel a deficit in my body that corresponded precisely with the oxygen output of a redwood tree. Still, I was a city kid. I basked in cutting-edge culture. I wore combat boots.

I wear clogs now.

The short version is that two young people who work at one of the richest and largest companies to ever exist paid me to leave. I don’t know what the young software engineers saw in my apartment. Maybe it was the famously ‘hip’ neighborhood named for the home of its original colonizers, men of god and cruelty, a loaded name that even in its contemporary incarnation had long ago ceased to represent anything to the seekers of authenticity who still made pilgrimage there to consume overpriced ice cream and convert the motley hues of the neighborhood into airspace . Maybe it was the exposed subfloors still pocked with staples from the nasty 1970s carpet I’d illicitly removed myself. Maybe it was the way the morning sun shone through the bay window and patterned the wooden door that I used as a writing desk. The young software engineers probably didn’t know about the piss smells, the screaming in the night outside, the earthquakes. But something made them want to trade places with me. I don’t know, maybe that’s just how young moneyed people acquire apartments: buy a building and pick it up and shake it until its occupants fall out. But it must have been worth it to them to at first threaten, then negotiate, then ultimately pay me many thousands of dollars to leave my home. It took years.

The messier version is that I saw it coming, and at times wished for it. Before the young engineers ever took a selfie of the skyline vista from the park down the block, I knew someone like them would be coming for me. I heard it in my old landlord’s increasing threats— I’ll just sell it , he’d say, if I needed the window fixed, if I wanted the paint above the bed to not peel, I’ll sell . I tasted the end in every bitter outing to a mediocre new restaurant I couldn’t afford, every friend who moved away. And I sensed it in the realization that every glance I gave every inch of my city had somehow become an angry glare, some twisted, tardy expression of a grief that I felt strongly for a vibe I couldn’t prove had been destroyed, even though its lack was evident in every empty storefront, newcomer’s complaint, grey paint condo flip. In many ways, I was already gone.

When I first prophesied the end of the apartment approaching, I also realized that I had a salaried job, uncharacteristically and probably for the last time in my lifetime, and so did my partner. And so we looked to the forest, the trees of my heart. Through a friend, we found the cottage with the wisteria and the big yard and the secret little room that would become the lair. We did the math. Weirdly, it worked. It worked better than renting, what can I say, shit is fucked up and bullshit. California! We qualified for a loan and signed a lot of papers we hardly understood. And unless society or the banking system collapses (likely), or the house burns down before then (also likely; I live in the wildland urban interface in California in the year 2021), the loan will be paid off when I’m 74 years old. (The loan will never be paid off.)

The timeline was messy. The foreseen events arrived. The landlord made good on the threat. The young engineer came knocking. We organized with the other tenants. We held out until it became time to let go. And that is how I came to live in—to “own”—a cottage in the woods in coastal northern California, and how I came to write inside the secret room.

I call the room The Lair because who wouldn’t. I wanted the lair to feel like the kind of room that wealthy men retire to after dinner to smoke cigars and talk politics, the kind of room the women aren’t allowed in—a Jane Austen, Lord Asriel kind of room. I wanted to fill it with books but also with things that I would normally never be attracted to in matters of home décor: deep hues without concern for natural light, velvety upholstery, dark William Morris wallpaper, carpets with colonialist pedigrees. I wanted rich-looking shit.

It turns out that I am not rich, and the room has very particular specifications. Crucially, the door to the lair is about a foot and a half wide and most furniture won’t fit through it. So the armchair is bright and cotton and Ikea, and I assembled it inside the lair like a ship in a bottle. The carpets are fake, ordered from an evil online mega-retailer I normally never shop at. The desk is tiny; I think my partner got it at Urban Ore salvage in like 2009 for like twenty bucks. The bookshelves are rigged from Elfa hardware and fresh fir planks that I had cut at the local mill and assembled myself. The standing lamp was my great-grandmother’s, and used to be kerosene. It alone looks like it might have illuminated one of those rich-dude rooms at some point in its life.

The rule of the lair is: no day-job work. No email. Internet research is okay, if it’s for a book. Movie-watching is not. Reading and playing guitar and daydreaming are encouraged. But no non-creative work. Ever. Abiding by these rules, the lair is where I finished the first draft of my first novel after ten years of working (and mostly not working) on it. But a big chunk of the next draft of the book wasn’t written in the lair, because it was written while I was evacuated from my house due to wildfires. California!

If the house doesn’t burn down, I will write my next book in the lair. If the house does burn down and we want to rebuild, we may or may not be able to, depending on whether our insurance is good enough (doubtful) and whether the property could be permitted for a new septic tank, the rules about which have become stricter on this watershed in the seventy years since the house was built, which is good for the salmon, and as goes the fate of the salmon, so goes the fate of the human race. I am not a salmon, I am a human with a high debt-to-income ratio, and so I have complicated feelings about all of this. The trees outside my office window don’t care about my feelings and for that I love them even more. Earlier this summer, some of the salmon were trucked to our creek from upriver because the waters everywhere are running hot and dry. The hope is that here in the shade of the redwoods, it’s possible to survive.

All photographs courtesy of Manjula Martin