Places Migrations

Manhattan’s Vanished Little Syria, and the Work of Preserving My Family’s History

Raji Lian, my great-grandfather, came over from Syria in 1899.

There is a winding street in Lower Manhattan called Washington Street. When I walked there in 2016, it was no more than a row of steel-grey office buildings and condos between TriBeCa and the Financial District, but in the nineteenth century, it was Little Syria. It was then a bustling marketplace, where Syrian and Lebanese immigrants peddled spices, linens, and pottery. Here, in the tenements where they lived and in the churches where they worshipped, they built their first community.

The first wave of Syrian immigration to the United States came in the late 1880s. Many of the immigrants came from Christian villages that were under Ottoman rule.

The distinction between Lebanese and Syrian back then was finer than it is now. Geographies have shifted since—what was “Greater Syria” is now Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, and the Palestinian territories. My family’s census records, taken at the turn of the century after they arrived, show both Syrian and Lebanese identification, with scattered “Oriental” here and there. We’ve always considered ourselves Syrian, though it’s not uncommon to hear the older generations use Syrian and Lebanese interchangeably.

The immigrants settled in the then-neglected area of Manhattan that is now TriBeCa. In 1946, residents of Little Syria received eviction notices, and the neighborhood was razed to make way for the Battery Tunnel. Now, it’s mostly forgotten. But for an enclave with such a relatively small history—fifty years—n a city with a long past, Little Syria was full of life.

In an 1899 article, the New York Times explored Little Syria, calling it “New York’s Syrian Quarter” formally but more colorfully describing it as the “tousled, unwashed section of New York” before noting its “gathering of Orientals.” It describes the dancing, the priests, and the wares of the merchant Sahadi, whose great-grandchildren still run the famous Sahadi’s Imports, a Middle Eastern market, and deli in Brooklyn.

I’m related to the Sahadis by marriage. The Sahadi name has stayed strong for over a hundred years, and I’m comforted by it whenever I browse their market shelves, filling up on pastries and grape leaves.

My family immigrated to Little Syria in 1899, the year the Times article was written. Raji Lian, my great-grandfather, came over from Syria with his three brothers and his father, Abdullah Lian. The brothers spent years as street peddlers before opening their own linen importing business, The Lian Brothers, while their father returned to Syria. I’m told that their last name may have originally been ‘Elian’, with the ‘e’ dropped for easier pronunciation, or because whoever was recording names at Ellis Island didn’t want to bother with it. It’s Lian now, kept strong by my aunt and uncle, a few other scattered relatives, and my mother, who hyphenated her last name after marrying my dad. And by a tattoo on the back of my neck, in the smooth blue-black Arabic of my grandmother’s name, Nancy Lian.

We have photographs of this first generation of immigrants, and it’s not uncommon for me to wake up to chains of emails passed along from my uncle to my mother with newly discovered photos, some of them delightfully candid. We’re always doing the work of preserving. One of my favorites is a portrait of Abdullah, the Lian patriarch, stern and mustached, in a late-nineteenth-century portrait.

Abdullah Lian, 1890s

He looks so severe, the way they did back then, and I try to match that with the description in the Times article, imagining him walking among the “tousled and unwashed.”

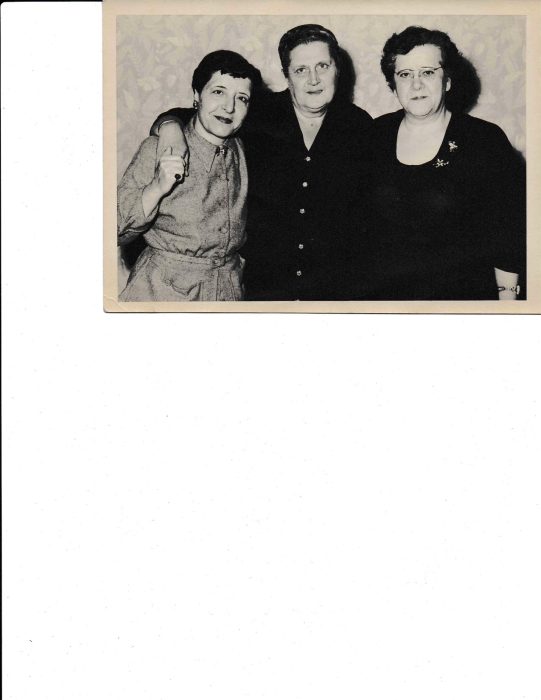

My favorite photos are of my great-grandmother, Rose, Raji’s wife, who looks so startlingly like my mother it’s uncanny. Unlike Abdullah’s portrait, Rose’s photos are full of life and motion. There are photos of her in bathing suits, sitting down at café tables, smiling mysteriously under a cloak of thick curly hair.

Rose Lian, 1950s

As my grandmother told it, Rose and Raji met in the cloakroom of a Bishop’s house, and whispered “I like you, do you like me?”, and they married not long after on Valentine’s Day in 1926.

Rose and Raji Lian, 1920s

The family didn’t live in Little Syria for long, and they eventually set up shop on Fifth Avenue, selling fine linens sourced from China, Portugal, and all over the world. It was a very successful business. My mother always said that if they’d bought the building that housed The Lian Brothers business, we would all be rich. In the post-war decline, people slowly stopped buying fine linens and the business began to fail.

When they weren’t working in Manhattan, they spent most of their time in Brooklyn, eventually settling in Bay Ridge, which still hosts a thriving Arab-American community. In fact, in the decades after 1946, when the residents of Little Syria received their eviction notices, Syrian communities expanded beyond the boundaries of Little Syria to Brooklyn, settling not only in Bay Ridge but also on Atlantic Avenue.

*

For Christmas last year, I received a book from my mom titled Strangers in the West : The Syrian Colony of New York City, 1880-1900, by Linda K. Jacobs. The book fell open in my lap to a page marked by a business card. The card listed the author’s name and contact info, and the page showed photos of my own family. Linda Jacobs had consulted my uncle in her research, and there, in a chapter titled “Who Were the Syrians?”, are two photographs of the Lians—the portrait of Abdullah that I love, and a group photo I’d never seen, from 1906. The book covers a great breadth of research, including labor statistics, census records, and first-hand accounts sourced from Syrian-Americans all over New York whose parents and grandparents immigrated at the turn of the century. I learn a lot: that the vast majority of Syrian immigrants came to the United States from Zahlé or tiny villages nearby in Syria, as did my great-grandfather. I learned that, like my family, many of the larger Syrian families with money began to move out to Brooklyn, though many still worked in Manhattan. Strangers in the West sits on my shelf as another touchstone to my family’s past, made all the more significant knowing that my family had a hand in its composition.

In studying early Arab-American culture and my own family history, my mom has always been my biggest resource. Last month in preparation for this essay, I asked her a few basic questions about our family’s history: When did our family start coming over to the US? What are some of her strongest memories of the older Syrian generations? Music? Speaking Arabic? Food?

Held within these questions is everything I knew and didn’t know about the Syrian side of my family, despite two decades of listening to stories and doing my own research. I knew that they immigrated around the turn of the century, and I knew that they eventually settled in Bay Ridge, where they would remain for generations. And I knew the food: grape leaves, hummus, heaps of mint and garlic in everything. Sweet-smelling lamb meat pies and my favorite, mujaddara, piled high with caramelized onions. I have an old picture of myself with my grandfather, sitting on the porch in our old house in Brooklyn, eating grape leaves that we rolled together. I remember hearing Arabic words in movies and asking my mom to show me how to sound out the beautiful guttural syllables. Despite my heritage, I have never learned Arabic.

The connections I have to the Syrian side of my family are both tenuous and unrelenting. Unrelenting because the older I get, the more important this half of my identity becomes, and tenuous because of how far away the history of it feels. My grandfather died in 1995, and my grandmother passed nearly fifteen years later. My mom has spent decades exhaustively searching old census records on ancestry websites, confirming places, dates, and faces with my uncle, who still lives in New York. One day, my cousins and I will be the ones left to do this—to keep the pictures, to cross-reference records. With every generation, we lose some truth, and family history becomes a game of telephone.

*

Back in 2016, the Downtown Community House at 105-07 Washington Street, one of the last remaining sites of Little Syria, was surrounded by buildings in various phases of construction. The Community House was vital to life in Little Syria, as it provided community programs, including food for malnourished children, free of charge. A few paces later, there was a sign in front of the construction site at 109 Washington Street, which used to be a famous tenement house. This was one of the sites that activists and historical societies petitioned the city to designate as a historical site for preservation. Recently, the building was demolished to make room for luxury apartments and offices. Then there’s St. George’s Chapel, where the predominantly Christian community of Little Syria worshipped. For the longest time, it was one of the oldest remaining buildings in the neighborhood. Now it’s a pub, and the single physical marker of what it once was is an engraving at the base of the building that is completely obscured by a water pipe.

St. George’s Chapel, 2016

There are still ongoing preservation efforts—the Washington Street Historical Society has been campaigning for years to convince the Landmarks Preservation Commission to designate areas of former Little Syria as historical landmarks. These three buildings: The Downtown Community House, the tenement, and St. George’s Chapel have all been described, in various articles and historical preservation campaigns, as “the last remaining markers of Little Syria.” These are places that had stood the test of time—testaments to where early Syrian immigrants lived, worked, and prayed. But most painfully, I think about all of the little buildings and shops that never made it to the twenty-first century, or even beyond the latter half of the twentieth. I feel heavy walking by where they used to be. I called my mom, who hasn’t lived in New York in decades, to tell her that the buildings were all gone, and she says nothing but, “Oh wow. Oh wow.”

*

When I ask my mom what she remembers from her childhood she writes something so beautiful in her email that I can only try to recreate it: “I remember the old records—glass, not vinyl—with beautiful Arabic music. And the food! Rose said she learned to cook from Raji. She never measured anything, so my parents wrote down her recipes by grabbing her hand to measure before she put anything in.”

Author’s mother and grandfather in her grandparents’ kitchen, 1971

The buildings in Little Syria have been torn down, but my mother’s Syrian family cookbook sits behind me, hundreds of miles away from her and a lifetime away from her parents, in my apartment in North Carolina. There are still no real measurements in it, and her own scribbled notes of “add ⅓ cup water, not a cup” or “needs more garlic” are hard to read but always comforting.