Things From the Magpie

From the Magpie (Work)

In which the Magpie finds direction in the grids of Agnes Martin.

Magpie, definition, Cambridge Dictionary: 1) a bird with black and white feathers and a long tail, 2) someone who likes to collect many different objects, or use many different styles

*

Put two fingers on the underside of your wrist. That is your pulse. It might feel a bit subtle, sometimes it does, but your heart pumps about two thousand gallons of blood a day. If you make it to, say, eighty, your heart will beat three billion times and pump a million barrels of blood.

Look around you, wherever you are. That one next to you, across from you, in front of you in line as you read this at the grocery store, the one you’re waking up next to, the one whose hair you’re braiding, the one who sells you a cup of coffee: within each one, a heart, a pulse that moves thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of barrels of blood, beat by beat.

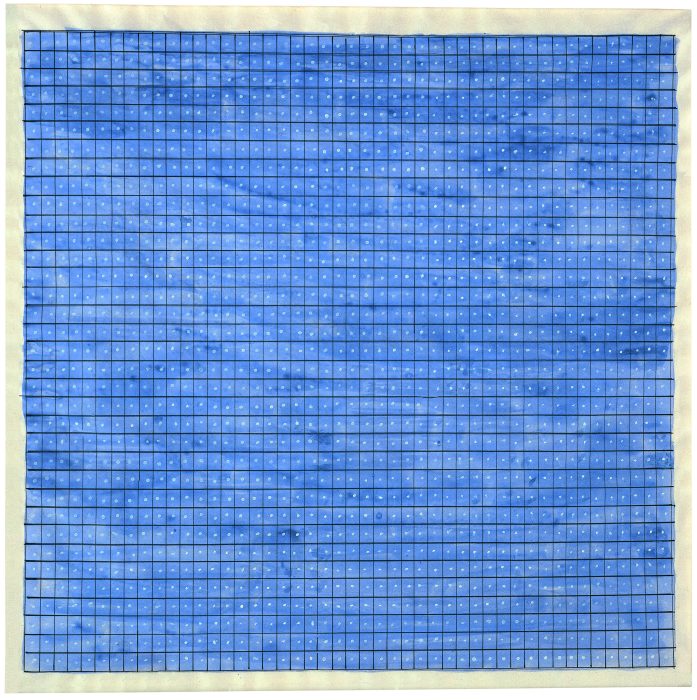

Now, go stand in front of an Agnes Martin painting. If you’re in New York, you can do this at the Guggenheim, but you can also go to the Fisher Landau Center for Art on a small street in Queens and see five exquisite Martins there. If you can’t go to either of these places, here, I’ll show you an Agnes Martin.

Agnes Martin, Untitled , 1960, oil on linen, 12 × 12 inches. © 2006 by Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

This one is “Untitled,” from 1960. The actual painting is a foot square, oil on linen. Her later works of this type tended to be much bigger, six feet by six feet. This one is from the earlier days of her working in grids, which she did for much of her career. Can you get closer to the screen? Do you see the way the lines move steadily down and across the page, none of them exactly straight, the color ebbing and flowing, beating, as it were, stronger or weaker? She didn’t use a ruler. She drew them freehand, every line. She was an odd woman, that Agnes. According to the biography Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art , by Nancy Princenthal, Martin lived alone all her adult life—in New York from 1957 to 1967, then Cuba from 1968 to 1977, then New Mexico from 1977 until her death in 2004. She was apparently schizophrenic. She didn’t paint from 1967 to 1973. If she didn’t like a painting, which seemed to happen fairly often, she cut it up with a mat knife. She liked to build herself adobe houses. She had relationships with women, but when Jill Johnston asked her about feminism, she replied, “I’m not a woman.” Many of her paintings have buoyant titles like “Little Children Loving Love” and “Lovely Life.” Here’s another of her paintings, from 1963, called “Friendship.”

Agnes Martin, Friendship , 1963, incised gold leaf and gesso on canvas. © 2015 by Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Like friendship itself, the work is at once ordinary, repetitive, closely woven, and magnificent. It just does not stop, stroke after stroke. It looks at once simple, effortlessly composed, and like an enormous amount of work.

If you look at the paintings of Agnes Martin, either padding down the sloping curves of the Guggenheim, or walking up the stairs at the Fisher Landau Art Center to a large, post-industrial gallery, or moving your thumb down this screen, you might feel the beauty of her vocation and her vocational devotion to beauty—indeed, beauty was a word that Martin used unselfconsciously. She once wrote, “All artwork is about beauty; all positive work represents it and celebrates it. All negative art protests the lack of beauty in our lives.” Her work was beauty, and her entire life was this work.

A friend of the Magpie’s, an actor, is fond of saying that when one is cast in a play, and in many other roles in life, “You know what the job is, but you don’t know what the work is.” It has occurred to the Magpie since the election that the converse is true: We do, actually, know what the work is, but we aren’t sure what the jobs are. There are so many. They cluster in our newsfeeds, like an unending stream of help wanted ads in a place desperate for workers: We need to call, we need to write, we need to march, we need to wear the safety pin, we need to take off the safety pin, we need to register, we need to mourn, we need to sign this petition or that one, we need to walk out, we need to help, we need to accompany our neighbors, we need to demand a recount, we need to dissolve the electoral college, we need to reorganize the Democratic party, we need to begin planning for 2018, we need to begin planning for 2020.

Questions:

a) Who is going to do all this work? b) How do you choose? c) How can we possibly get it all done?

Answers:

a) we are b) it doesn’t matter, because it’s all necessary c) we won’t, but we will do it, anyway.

The Magpie apologizes for what may seem like a schoolmarmish tone, but these aren’t ordinary times and the Magpie is just as freaked out as anyone else, as everyone else.

The Magpie, just like you, needs to figure out a way to get through this.

The Magpie, ever attracted to what gleams in the world, sees this, today, in the work of Agnes Martin: the work of beauty, and the beauty of work, which is like a pulse beating across and through her paintings, line after line, grid after grid, crossing after crossing, canvas after canvas, year after year, for her entire life as an odd woman who wouldn’t have said she was a woman at all. We’re all looking for a hero and a way to be as history sweeps us up, reminding us—how did we forget?—of its vast, heedless power. This is mine.

Dear ones, I am so glad of your friendship. To be quite frank, I feel that some of us had lost touch over the years. It had seemed as if we were so divided, but now we find ourselves on the same grid, perhaps it is a net, perhaps it is a fence, perhaps it is a house with many windows, pulse to pulse.

I’ve missed you. We have beautiful work to do.

photo by George Etheredge for The New York Times