Fiction Short Story

The Longest Trial

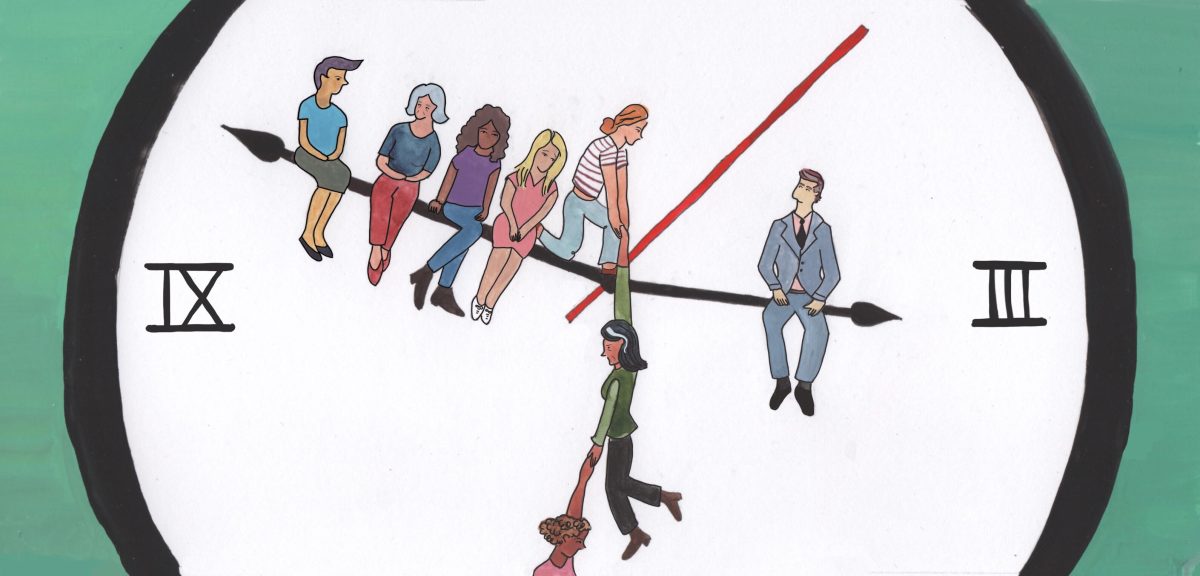

There were eighteen thousand two hundred and fifty victims, one per day over the course of fifty years.

There were eighteen thousand two hundred and fifty victims, one per day over the course of fifty years.

It was decided that the trial of the predatory film director would be held in Madison Square Garden to accommodate the numbers. Someone with connections at the Garden hooked them up and the judge’s bench was set up in the middle of the boxing ring left up from a match the night before.

The judge was a woman who had briefly been an actress in the late ’80s, had an experience that left a bad taste in her mouth, and decided to go to law school instead.

The attorney for the prosecution was a woman who had never been an actress but had begun her career on Wall Street, had an experience that left a bad taste in her mouth, and decided to go to law school instead.

The attorney for the defense was a woman who had never been an actress but thought about it for a minute before scrapping the idea and going to law school instead. She had been harassed in tenth grade by her science teacher and disbelieved by the school principal, who told her his reputation was spotless and that she was surely mistaken . The attorney for the defense knew that she was not mistaken, but in that moment, her rage spun around toward women and stayed there.

The bailiff was a woman who had never been an actress but once dressed up as a sexy bailiff for Halloween and regretted it for multiple reasons.

The deputy clerk was a woman who had never been an actress but had once gone to a Halloween party dressed as a giant sexy pumpkin because she thought it would be funny. A guy at the party, observing some assholes bothering her, told them it wasn’t okay, chatted with her long enough for her to notice his earnest brown eyes behind his Clark Kent glasses (the totality of his Superman costume), and walked her to her car afterward, only to jerk off at her in the parking lot after she closed her car door.

The court reporter was a woman who had never been an actress but at her very first job out of college, her boss often called her at home because he liked her so much and had thought of something funny he just had to tell her—usually one more thought about a female co-worker’s “getup,” usually about what he thought she might be asking for by wearing such a “getup.” These “getups” had nothing discernible in common to the court reporter other than her boss noticing them.

The court interpreter was a trans woman who had been harassed ever since she was in first grade and went to school wearing purple nail polish. Her stories did not get better from there.

The court security guard was a woman who had never been an actress but was alive in the world.

The jurors were made up of three men and three women, none of whom had ever been actresses.

The public in attendance was mostly made up of women, only a few of whom had been actresses. The public in attendance had been: catcalled, critiqued, ogled, touched, patted, palmed, and pressured; they had been groped and grabbed, massaged and manipulated; they had been fingered, fondled and followed, stroked, squeezed and stalked; they had been called prudes and sluts; they had had their lives or their jobs threatened in person, by phone, by mail, by email; they had been trolled online and been called bitches and whores offline; they had had to repeat the word No under any number of unacceptable circumstances; they had had to walk past the porn site open on your desktop at work; they had had to listen to you talk about what you thought of other women and their bodies and their behavior; they had suffered countless offenses both subtle and not; they had been told to smile.

There were some men in attendance. Not a lot, but some. Some of the men were there to support their partners. Some of the men wanted to support women. Some of the men had their own stories. Some of the men were there to pick up women, let’s be real. Those men did not fare well.

*

The first part of the trial lasted for ten years. Each day allowed for five of the 18,250 accusers to give their testimony. Their stories had some widely varying specifics that were relevant to them as individuals, and a lot of extremely similar specifics that were relevant to the defendant’s behavior. The attorney for the defense asked each one of them the same initial questions: What were you wearing when you met him, why did you agree to meet him, where did you meet him, what time did you meet him, were you drinking or on drugs when you met him, what was your height and weight at the time of the alleged incident, how old were you at the time of the alleged incident, did you give nonverbal consent?

Early on, the attorney for the defense spent several hours questioning one woman about the down coat she had been wearing at the time the defendant approached her. What color was the coat? How long was the coat? What size was the coat? Did the coat open and close with a zipper, buttons, what? Did you ever open the coat? Were you wearing anything under the coat? How do we know for sure you were wearing anything under the coat? Can you see where such an oversized coat might cause the defendant to fantasize about what was under the coat? The witness described the coat as a knockoff Norma Kamali sleeping bag coat, at which time the attorney for the defense interrupted the witness mid-sentence, repeating the phrase Sleeping bag! A sleeping bag coat! as though everyone knew what really went on in a sleeping bag, and what was therefore implied by the wearing of such a coat.

In an ordinary trial, the credibility of the witnesses relating to these and other matters would have been similarly picked apart, but due to the exceptional number of witnesses in this case, the judge made a decision, post-sleeping bag coat, to limit testimony and cross-examination to thirty minutes for each. As a result, the attorney for the defense quickly became proficient in sarcasm, mocking laughs, head shakes, and pointed glances at the jury.

There were only three witnesses for the defense, each of them an A-list movie star, all men, so that only took one morning. These women all showed up for this, said movie star number one. They participated voluntarily , said movie star number two. Movie star number three started by saying, Listen, I was there, before he realized he might be digging himself a hole.

The attorney for the prosecution asked each of them if they had ever heard rumors. Movie star number one said he paid no attention to rumors. The question was whether or not you heard them , said the attorney for the prosecution. Movie star number two said he had heard them, but that he’d also heard plenty of rumors about himself that weren’t true, so he had no reason to believe any rumors ever. Movie star number three tried to frame his answer around separating the art from the artist, which did not go well for him.

The defendant also took the stand. The attorney for the prosecution began by asking him if he had met any of the 18,250 accusers present. Absolutely not, he said.

Not one of them? the attorney for the prosecution asked. She produced a thick file of photos of him talking to over a hundred of them on separate occasions and dropped it on the witness box in front of him.

The defendant opened the file and looked at the first photo. Well, maybe at a party for five minutes. Nothing I’d remember.

So, let me understand, the prosecuting attorney said. Y ou’re saying that these eighteen thousand two hundred and fifty women have not told the truth. Under oath.

That is correct. I am saying that all these women are lying cunts. I would spit on each one of them, if I didn’t have a salivary gland disorder that prevents me from doing so.

Nothing further, your honor.

*

The jury deliberated for ten more years.

From the beginning and for the entire ten years, the women on the jury, reviewing what they believed was overwhelming evidence, were unanimous in favor of guilt. The men, for many of these years, were unanimous in their inability to let go of their reasonable doubt.

The women went through the testimony of each and every one of the eighteen thousand two hundred and fifty witnesses for the prosecution, pointing out the similarity of their experiences. The men went through the testimony of the three movie star dudes by saying These guys said they had no idea .

The women went through each one of the 18,250 testimonies again, trying to tweak their language so the men could better understand. The men suggested that the women could have known each other; that they could have agreed on a story.

The women clenched their jaws, patiently explaining the improbability of 18,250 strangers coordinating such a thing.

One of the men finally changed his vote after having a longer private conversation with one of the women during their lunch break. He asked her if she’d ever been harassed, and she said, I was born, so yeah . She told him a story about how she broke up with a guy once because his friend tried to hit on her and his only response was I’m staying out of it , at which time she told him he could stay out of her, too. It was at this point that this male juror started thinking about how many women he may have unintentionally harmed over the years, simply by saying nothing. In truth, he was an okay guy who hadn’t actively harmed anyone, he’d just never, you know, thought about whether being a woman in the world was maybe different from being a man. The okay guy wept, on and off, for the duration of the trial after this. The woman who led him to this weeping epiphany had to resist a small urge to console him, having new, tender feelings toward the okay man; she thought maybe, in a few years, if the trial ever ended, she could date him. Ultimately, he thought she was too old for him to date, even though they were the exact same age.

The three women plus the okay man went through each of the 18,250 testimonies once again, and finally a second man on the jury changed his vote, but mostly because he was tired of living in the skybox and wanted to go home. The three women plus the okay man went through each of the testimonies again while the second man napped in a Barcalounger.

The third man on the jury believed the big movie stars, and could not get past the phrase “reasonable doubt.” Those men were there and they didn’t see anything . I don’t know any of those women. It’s not that they don’t seem believable, but how would I know if they’re telling the truth? He said it was still basically he said, she said . It was pointed out to him that it was actually he said, she said times 18,250.

Would there be a number of women that might take away your doubt?

The last juror didn’t have an answer. Even his shrug was half-hearted.

*

Twenty years in, the jury was still deadlocked, their health was on the decline, and the defendant, then in his late nineties, had been confined to a bed several years earlier with severe dementia. This was a massive bummer, obviously, for the 18,250 who hoped he’d rot in prison.

Twenty years in, many other harassment cases had gone to trial, ones with fewer witnesses that allowed for more timely justice. A couple new laws were passed. Some people changed their views; some didn’t. The president was finally impeached in his second term, even though it wasn’t on account of him being a predator, and three more white male presidents were elected.

Near the end of the twenty years of this trial, the deadlocked jury tried one last time, and one last time Reasonable Doubt Guy again would not budge on his vote. He said, I will die before I change my mind on this , and he promptly died.

The judge told the alternate juror to cast their vote; that juror (who not for nothing had the patience of a saint this whole time having to listen without speaking) voted, and their vote made it unanimous. There were parades. Many of the survivors had died by the end of the twenty years of this trial, so the parades were small, but there were parades.

Madison Square Garden had fallen into disrepair during the twenty years of the trial, and was never again used for any other public event.

The judge died not long after the trial ended. She was ninety-four. The corner of Thirty-third and Seventh was renamed in her honor, but you know how that goes. No one calls Sixth Avenue “Avenue of the Americas.”

The attorney for the prosecution lived long enough to see some of those horrible Wall Street dudes go to prison, but she died alone in her penthouse apartment eating a TV dinner in front of a Golden Girls rerun. Very few people who were invested in this trial had much time, let alone interest in relationships. At one point or another, they all knew it was about the future.

The attorney for the defense had one of those potentially life-changing experiences that usually only happen in the movies, after the son of the school principal (who had died long before) tracked her down to tell her that his mother had expressed great remorse and shame about defending the teacher who had harassed the attorney for the defense in high school, causing the attorney for the defense to weep, and there was a tiny little window in this weeping where she felt something like forgiveness, but it was too new and too large of a feeling, and she sensed that holding this already large feeling would lead to further feeling, and who knew where that might lead. So she pulled herself together and went on as before, until one afternoon, on the renamed corner of Thirty-third and Seventh, of all places, the attorney for the defense approached a woman in a down coat. The coat was bright red, dramatically large, the largest coat she’d ever seen, and the woman wearing the coat had a wavy silver bob, bright red lipstick and a serene, confident presence the attorney for the defense wished she’d had for just one day of her life. The attorney for the defense stopped the serene, confident woman to compliment her on the coat, and the serene confident woman thanked her and told her it was vintage Norma Kamali. Well, knockoff Kamali , she said. Recognition ensued, and they embraced, and the two women understood this moment as something bigger than forgiveness; it was a blessing.

The bailiff joined a trauma survivors support group about nine months into the trial and continued to go for the duration, which helped a lot. She met a lot of the witnesses there over the years, which could have been a weird conflict, but it was an anonymous group, so they gave each other knowing looks of support when they saw each other. At the end of each day, they group-texted flexed-bicep emoji in all the skin tones.

The court reporter wrote a bestselling memoir based on her experiences dealing with men in her personal life outside the trial. It got numerous shitty reviews from men, but she cared not.

The court interpreter, about a year in, was like fuck this , and went back to school to become a high school guidance counselor. The court interpreter got a degree and then got a job at a high school in Nyack, where she felt purposeful for the first time in years.

The court security guard had the good sense to quit while she was ahead, took a long vacation at a spa in Palm Springs to regroup, and ended up buying a shack in Joshua Tree. She’d been a desert person this whole time and never knew, and something about rocks and cacti turned everything right around for her. She died alone watching The Golden Girls , too, but in a good way.

The okay man from the jury never met a woman again without first saying he was sorry for having stood by silently while the patriarchy raged on. It was literally how he introduced himself: Hi, I’m Joe, and I’m sorry for having stood by silently while the patriarchy raged on. It was a bit much. Joe the okay man went on a couple of dates with a woman he liked very much who was also his own age, but he was still processing and also by now had an idea maybe not to mention the age thing.

The deputy clerk went to therapy, and some years later she ran into the okay man, who said the thing he always said, and she told him to cut that shit out, just do better. He called her a couple years after that, and the deputy clerk and the okay man, who was a better man by this time, began dating. They fell in love and, as they were too old to have kids, decided to become foster parents to a teenage girl. She grew into a spectacular young adult who had a few, just a few less shitty things to deal with in the world.

The witnesses for the prosecution, those who lived to see the end of the trial, had among them: 8,746 divorces (also about the same number of marriages and remarriages), 3,105 facelifts that were admitted to, several prescription pill addictions (many due to back pain from sitting in the arena chairs for twenty years), dozens of kinds of cancer, and countless career regrets due to showing up for their sister survivors every day for twenty years rather than going back to work. Let it be known, though, that this was no small thing, this solidarity; that it was a significant and lasting consequence of the whole, lingering trial, for themselves and for the world, that these women held each other up, sometimes very literally because they were so old that many literally could not stand on their own, and when the last of the 18,250 was finally gone, their daughters and granddaughters took it from there.