Fiction

| Short Story

Baretta Number 23

The windows of the stone Victorian mansions across from Chestnut Hill High were reflecting the orange glow of the setting sun. Chase Murray, sophomore, was wearing an American Eagle gray hoodie covered by his blue football jersey, the number 32 in gold on his back glowed from the bounce-back of dusk. The air was unusually […]

The windows of the stone Victorian mansions

across from Chestnut Hill High were reflecting the orange glow of the setting

sun. Chase Murray, sophomore, was wearing an American Eagle gray hoodie covered

by his blue football jersey, the number 32 in gold on his back glowed from the

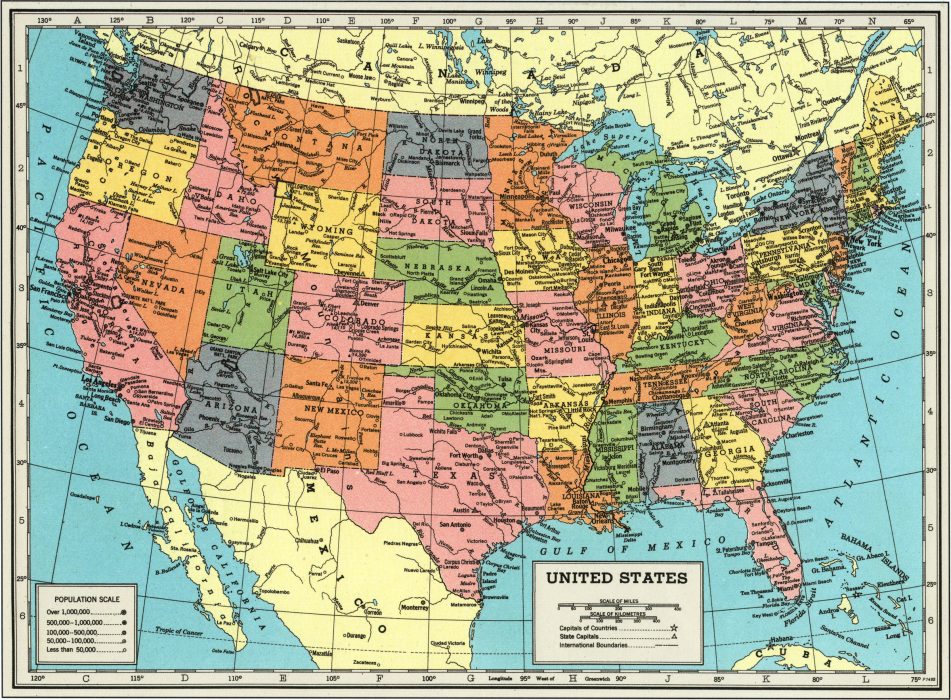

bounce-back of dusk. The air was unusually chilly for early October in

Pennsylvania, so he kept his hands in the pocket of his jeans, pulled the hood

over his head, and stared at the row of windowless doors, the school’s entrance,

waiting for his older brother Trevor to come out.

Chase wasn’t Trevor’s younger

brother—he was his own man. He wrestled in the winter, played baseball in the

spring, and volunteered all summer at Mount St. Joseph’s Church in the food

pantry feeding those in need. The past summer he’d cleaned the rectory every

Saturday night, but not anymore. He’d decided a few weeks ago he just couldn’t keep

doing it.

Trevor came out of the building, his

green L.L. Bean backpack slung over his left shoulder, the tail of his sweaty

nylon jersey sticking out of the half-zippered pocket, keys dangling from his

mouth as he put his sunglasses on. He walked by Chase, who was no longer

looking at him, and jerked his head motioning for his little brother to follow.

Chase walked behind him regardless.

“Call Me Maybe” played quietly from

the radio as Trevor started the car.

“You were good today, Smiley,”

Trevor said. “You’re going to be the next Brent Celek.”

Chase closed his eyes and rested his

head on the seat.

“I’m serious. By the time you’re my

age, you’re going to have scouts looking out for you.”

Chase sat there, eyes closed, silent.

“Why’re you so quiet?”

“I’m just tired,” Chase replied, still

not opening his eyes.

“You want pizza tonight,” Trevor asked.

“No. Just want to take a nap.”

Trevor was getting tired of Chase’s

teenage angst. It’d been a little played out since the summer. Yeah, yeah,

being fifteen is really hard. Try applying for college.

The car ride was short enough to

play all of Carly Rae Jepsen and the first verse of Gotye’s “Somebody That I

Used To Know.”

Their parents weren’t home. They

were away on a vacation for two in Dollywood—Dawn always wanted to visit, and

Trevor Sr. just wanted time with his wife again. Once they parked in front of

the garage doors, both boys got out, grabbed their gear, and walked up the

slate stones to the front door.

Chase walked to the bedrooms

upstairs while Trevor popped off his sneakers, dove onto the sectional, and

whipped out his cell phone. American Dad

was on TV, muted, as Trevor called his buddies to see if they wanted to head

over and play some Call Of Duty: Black

Ops II—no takers. Tuesday was not a night out. The guys liked to save their

energy for the beers and Belvederes in the woods after Friday night games.

Trevor thought to himself, “What

kind of idiots don’t go over their buddy’s house when their parents aren’t

home? Oh, I know—pussies!”

As he went into the kitchen to

microwave a pepperoni Hot Pocket, the unmistakable sound of his father’s Beretta

92 reported. It was unmistakable because Trevor’s father had not only taken the

boys shooting with it several times, he had also told them where the gun was

hidden, where the key to the lockbox that held the gun was, and how to defend

themselves just in case.

“What the—”

Trevor stormed upstairs yelling,

“Dad is going to fucking kill you when he sees—”

And what Trevor saw was not in his

parents’ bedroom. He had not gotten to the end of the hall to see his brother

sitting on their parents’ bed with a smoking pistol in his hand and a bullet

hole through the ceiling. He was no longer mad. He was no longer ready to beat

the crap out of his brother for screwing up the house while mom and dad were

away. He was no longer thinking of excuses to get himself and his brother out

of a year’s worth of groundings, nor was he wondering if his parents would ever

trust him enough again to ever leave him alone in the house.

What he saw was in his little

brother’s room. But it wasn’t the kind of memory anyone wants to supplant the

images of waking a baby brother on Christmas morning to tear wrapping paper

from Transformers; of scaring a little brother as he walks out of his room the

night before Halloween; of breaking the bed as you wrestle your little bro into

tapping out. This was an image of a little boy blowing his brains out and doing

it right—the barrel jammed against the roof of the mouth angled so perfectly as

to leave no part of the back of the head, or the brain, intact.

Trevor was frozen. He didn’t move

for a while, but when he did, he pulled his phone out of the pocket of his blue

sweatpants and dialed nine-one-one. He didn’t remember what he said, didn’t

remember the police or the ambulance arrive, didn’t remember his parents

crying, blaming him, blaming each other—but he remembered what he saw, only

remembers what he saw, whenever he thought of his little brother, number

thirty-two, the happiest kid in school who was always, always smiling.