Don’t Write Alone Interviews

Pyae Moe Thet War Knows What Makes a Good Essay

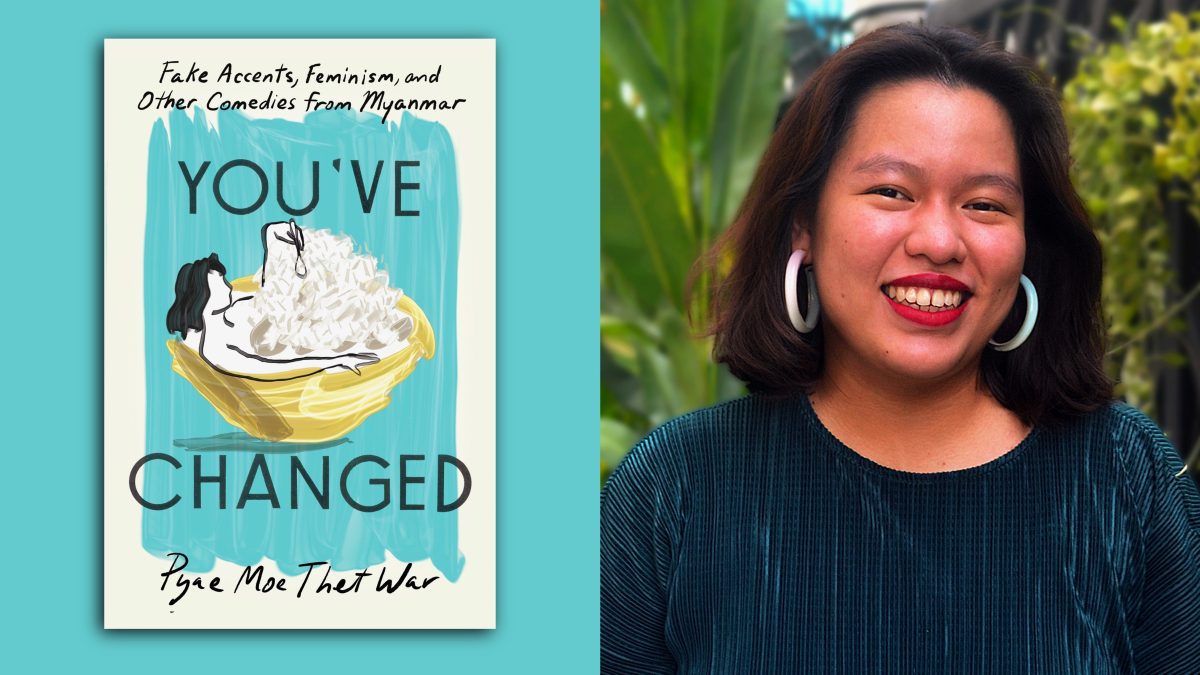

In this interview, Tajja Isen talks to Pyae Moe Thet War about her new collection ‘You’ve Changed,’ finding her voice as a writer, and publishing a book on her own terms.

I first learned of Pyae Moe Thet War’s work nearly a year ago, when she pitched me a column about baking and creativity. In our correspondence, I was immediately struck by the playfulness of her voice and the confidence of a debut author stepping up to disperse the mysteries that float, miasma-like, around the publishing industry.

The pitch eventually became this essay on how publishing your debut book has a lot in common with baking croissants—both are messy, finicky processes that distill a staggering amount of work into a polished product. They’re also both undertakings, Pyae argues, in which it’s customary to talk more about the outcome than the work it took to get there. By obscuring that work, we risk missing vital lessons about the often unglamorous efforts required by creativity. “Outside of the publishing industry,” she writes in the essay, “We [don’t] spend enough time discussing the labor behind writing a book.” Similarly, as someone who works outside the baking industry, I did not know how much work goes into making croissants until I edited that essay. The process struck me as incredibly tedious, but I suppose a baker would say the same thing about what it takes to publish a book. How many of us can do both?

Pyae Moe Thet War can. She is a writer, a baker, a cultural critic, a teacher , a swimmer, a Myanmar millennial, and a generous literary community member. She is also the author of You’ve Changed: Fake Accents, Feminism, and Other Comedies from Myanmar , one of my favorite essay collections this year, which is published today. Back in early March, Pyae and I chatted over Zoom about craft, humor, navigating the publishing industry, and how to put out a book on your own terms.

*

Tajja Isen: How are you feeling at this stage of the publishing journey?

Pyae Moe Thet War: I am scarily calm [at] this moment. I’m trying not to think about the fact that people that know me in real life will read this book. I’ve let one friend read an advance copy—my copy—and that’s it. I haven’t let anybody else read it. My general rule has been, “Once you read the book, you can’t talk to me about it. Even if it’s a compliment. Don’t even read it in front of me. We cannot acknowledge the existence of this between us.” I grew up being the little writer who turned to writing when I couldn’t talk to people; the things I was afraid to say, I would just write them down. And now it’s going to be published. People will find out what I’m thinking, and it’s scary, but I’m trying to stay calm about it.

TI: You mention in the book, as you alluded to just now, that you’ve been working on some of these essays for a long time. How did you find the throughline that took these discrete pieces and turned them into a book?

PMTW: In the very early stages, when it was just my agent and me, one general theme that we decided on was self-acceptance. I know that’s a really broad theme, but it was good to keep in mind. But I also think—I forget who it was, but I remember a while back, on Twitter, a writer tweeted something about, “Is there a common question or theme that, as writers, you find all of your work comes back to?”

I think I’m one of those writers that, in all of my writing, consciously or not, is always circling the same themes. TI: Jess Zimmerman ! “If your writing had a refrain, what would it be?” I love that tweet .

PMTW: Yes! I used to have this fear that all of my writing would be redundant and repetitive, as if [I was] always saying the same thing, but through this book, I’ve realized that’s a good thing. With each essay, I would find myself circling through these themes of self-acceptance, home, language, and love. For me, [cohesion] did come very naturally. I know some authors write essay collections and some essays don’t make the cut. But for me, all of them [did]. The only thing my editor and I really tweaked was the order of the essays. I think I’m one of those writers that, in all of my writing, consciously or not, is always circling the same themes.

TI: That makes sense to me, because your essays all feel very cohesive, not just in subject matter, but in voice. You have this very assured, very distinctive voice, and you’re very, very funny. I would love to hear about how you approach bringing humor to the page.

PMTW: When it comes to my writing, that is genuinely one of the biggest compliments. I studied literature growing up, and I was definitely one of those lit students who thought—especially because I’m a brown woman and was surrounded by these white lit bros using fancy words and sentences that were a page long—I wanted to write like that. I thought, it’s not good if somebody understands what my writing is saying. It’s too simple. Now, I realize that my writing style is that I basically write how I speak. It’s very conversational, and I’m proud of that now. But for a long time, I was really fighting it—I wanted to sound very smart and academic on the page. As I’ve gotten older and more experienced [I’ve] realized, “Hey, actually it’s not so easy to write conversationally, to write with humor.” So I’ve leaned into that.

My editor, Megha Majumdar, is amazing, and the humor was also one of the things she picked up on from the beginning. I did not think I had a funny voice, or that I was writing a funny book. I was just writing how I speak. If anything, I was worried that my little quips or sarcastic remarks would be cut [for not being] serious enough. Growing up as a non-Western brown woman writer, I [thought], “Oh I have to have a very serious voice,” even though that’s not who I am as a person. I really had to get rid of that [belief]. One of the biggest pieces of editorial advice that Megha gave me, which was super-helpful, was saying, “When you’re editing this, think if you would talk like this to a friend.” In my earlier drafts, there would be points where it would sound stilted, and it wasn’t how I would speak, so it wasn’t how I would write. I wanted to feel like I was talking to a friend, so that’s what I was trying to keep in mind as I was writing.

TI: I want to go back to something you mentioned about the expectations that are placed on racialized writers, on non-Western writers, on Myanmar writers. I was so interested in how you built that awareness into the book, especially in the essay “Unique Selling Point.” First of all, how do you navigate that on the page, and second, how are you dealing with it at this stage of publication?

PMTW: When I handed that essay [“Unique Selling Point”] in to my agent, before we even went out on submission, I thought, basically, Did I screw up my chances? I mention in the book that, in my first meeting with her, I made it clear: I don’t want this to be a quote-unquote “political book”, or a “race book,” or a “Myanmar book.” I know there’s no escaping that, to some extent. Publishing operates under capitalism. You want to sell books, books are commodities, and there are trends. I don’t have anything against people in publishing who work in sales and marketing whose job it is to look at data and research; those are very important jobs, and I get why they exist. But if certain writers who look like me, or have names like mine, are only allowed to write certain books, and [people] think “Oh, we can’t take a risk on a book that’s not a ‘race book’ because we don’t have evidence that it’ll sell”—it’s like, you’ve never taken the chance. It’s a catch-22.

TI: The absence of evidence being the evidence of absence.

PMTW: Exactly! And it was so scary. It is so scary. I tell people, if somebody picks up this book thinking it’s going to be a rundown of Burmese history and Myanmar history, they’re going to be very disappointed. But I’ve been very fortunate to be honest about it from the beginning and trust that the right people will have the same vision as me. That’s so scary when you’re a writer of color, when you’re a non-Western writer, when you have zero connections to this industry. It is terrifying for me to be like, “This is what I want. This is how I want to market this book.”

Growing up as a non-Western brown woman writer, I [thought], “Oh I have to have a very serious voice,” even though that’s not who I am as a person. I know that I will never be able to escape the label of “this is a Myanmar book,” and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. But I don’t want that to be all it is. So when someone points out, for instance, the humor in it, that makes me really happy. Because, [in] so many books by writers of color, it’s all about the struggle and it’s really dark and sad. Those books are important, but for me, I wanted this to also bring joy and make people laugh and talk about things like baking, and swimming, and literature, and stuff like that. So, just being honest with myself and people I encounter, both on my team and throughout this process, about what I want it to be. And holding firm to that no matter how scary it can be. And it can get really scary, because you do think, Oh no, did I just screw up my chances of getting a book deal, or getting represented?

TI: That you build those conversations into the book is such a service to emerging writers and to people who are thinking about putting together a book proposal—to know that that’s the industry, that’s the challenge, but this is how you’ve decided to tell your story and these are the principles you’re going to hold firm to. I have tremendous respect for you for doing that. Because it’s hard.

PMTW: It’s so hard!

TI: The way I sometimes think about it is, you write a book, and you have your content and your form. A dominant tendency in publishing when it comes to work by writers of color is to neglect the form and talk about the content, or talk about the writer’s identity as if it forms the entirety of the content.

PMTW: I remember one particular editorial call with Megha where I talked to her specifically about this. She encouraged me to reach out to other Myanmar writers and talk to them about their experience publishing books, and that really helped. I get why, for me, coming from the background I do, living in a non-Western country, you do think, What if this is my one shot? At the end of the day—and this was so scary to admit and accept—I would have rather this book never get published than have it published on somebody else’s terms or have it marketed in a way that I just wasn’t comfortable with. I don’t think I could have lived with myself if that was the book that came out with my name on it.

TI: I want to switch gears and ask you about craft. I’ve had the pleasure of editing you twice for the magazine and both times they’ve been writing- and craft-focused essays. What draws you to craft pieces? Maybe you want to touch on your teaching as well—I was so excited to learn that you’re going to be teaching a class for Catapult!

PMTW: [Laughing] I’ve just completely embedded myself into the Catapult ecosystem!

TI: It’s what we’re here for!

PMTW: I’ve got to be honest: when you accepted a craft essay from me, I was kind of surprised because, for a while there, I didn’t think I knew anything about craft. I studied creative writing, so I’ve taken workshops, but I used to think that for personal essays—honestly, I used to think they were easy to write. For me, to an extent, they are easy to write. Melissa Febos has the book Body Work , and it’s about writing the personal and how a lot of people view it as “navel gazing”—and a lot of people do think it’s easy because you’re just writing about your life! I think a lot of that really warped my perception of my craft. Because I didn’t think about it as craft. I just thought, “I write essays about myself and things that happened to me.”

But I know what makes a good essay; I know when something isn’t working. Self-editing is so hard, right? You have to really be a master of your craft to be a good self-editor. It’s so difficult to look at your work and say, “I don’t think this is working, but I don’t know why. Something isn’t right.” Then I’ll ask: Is it structure, is it language, are there too many threads, not enough threads? I’ll go down to the details and delve deeper. But, at the first step, it’s just a gut thing. If something isn’t working, it just nags at me. I’ll be lying in bed in the middle of the night, literally thinking, That paragraph, there’s something wrong with it. It’s just not working.

TI: I have one more question: Not to be creepy, but I saw you tweeting about having finished a manuscript draft . What are you working on next?

PMTW: It’s very early stages, and it’s not nonfiction—it’s fiction. I feel like I’m nonfiction-ed out for now. I’m definitely open to writing another essay collection in the future, but writing fiction is something I’ve been wanting to do for a while. It’s very difficult. I’m trying to remember this is my first time writing a whole manuscript of fiction, and I’m trying to keep it in perspective: I’ve been writing nonfiction technically since I was sixteen, so, about a decade. I have the skills of a ten-year-old when it comes to nonfiction in comparison to the skills of a one-year-old in fiction. It’s like I’m starting all over again. But it’s just fun. That’s true with everything I’ve done—I always make sure I’m having fun and that it’s something that I want to write. I wrote this book, You’ve Changed , for me. At the end of the day, it was something I wanted to do, that I wanted to write, wanted to read. It’s the same for the manuscript that I’m drafting, and I want it to be true for all of my projects.